Curlew are a priority species of conservation concern in the UK due to a recent severe and rapid decline in population. The effects of tree planting (afforestation) on breeding curlew and other wading birds are not yet fully understood, but research so far suggests that there are negative impacts. England introduced an afforestation policy in 2022 to deal with these concerns. This briefing sheet introduces the issues and summarises the science for people of all backgrounds with an interest in curlew conservation.

Introduction to curlew

The Eurasian curlew (hereafter ‘curlew’) is the world’s largest wader, recognisable for its high-pitched ‘cur-lee’ call, long legs, mottled brown plumage, and slender curved bill1.

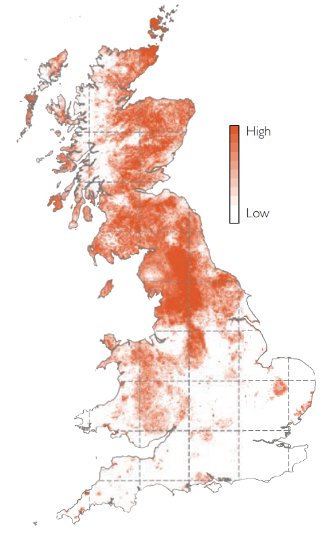

| Breeding population | UK: 58,500 pairs2 England: 30,000 pairs3 |  Relative abundance of breeding curlew in the UK Bird Atlas 2007-11 © BTO |

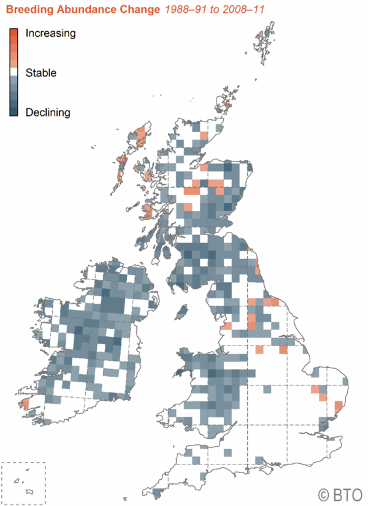

| Breeding population trend | UK: 48% decline between 1995-20204 England: 29% decline between 1995-20204 | |

| Diet | Soft invertebrates such as worms, larvae, shellfish and shrimps1 | |

| Habitat | Summer: Upland moors, lowland heaths, bogs and wetland, rough pasture and tussocky grassland1 Winter: tidal mudflats, saltmarshes and coastal grasslands1 | |

| Nesting habit | Four eggs in cup-shaped nest amongst vegetation on the ground5 Breeding season: April-July5 Incubation period: 4 weeks3 Hatch to fledge: 5 weeks3 | |

| Main predators | Foxes, corvids, mustelids6,7 | |

| Conservation threats | Predation6-8, agricultural intensification9,10, afforestation11-13, disturbance14 |

What is the conservation status of the curlew?

Historically, the curlew was widespread and common in England, breeding in marshes, meadows and arable fields as well as on moorland15. National breeding bird surveys have shown that since 1995 there has been a 48% decline in the UK’s curlew population and 29% in England (see Figure 1)4,8.

Curlew in England are mainly concentrated in the Pennines, and in the North York Moors, Cheviot Hills of Northumberland, the Peak District, and the Forest of Bowland16. In southern England, only a few hundred pairs are breeding in remnant populations on the lowland heath, wetland and grassland of the New Forest, Somerset Levels, Shropshire Hills, Brecklands and Thames marshes3. There is a very real risk that curlew will be lost as a breeding species in lowland southern England18.

Curlew are designated as a Section 41 Priority Species in England17 and are listed on the UK Red List of Birds of Conservation Concern. The UK is home to over a quarter of the world’s breeding population3 and therefore has an international obligation to protect the species from further decline8.

What is driving the decline in curlew?

Urgent scientific research has been conducted around the UK and Europe to find out what is responsible for the steep decline in curlew9,20. A review of nest monitoring studies in Europe found that breeding success was so low from 1996-2006 that over 70% of nests were not able to hatch a single chick9. Of the chicks that did hatch, half survived to fledging9.

Long-term ringing programmes suggest that adult survival is very good at over 90%21. Therefore, the data indicates that the main driver for curlew population declines is poor breeding success, due to losses of nests and chicks20,22.

Threats to curlew nests |

|

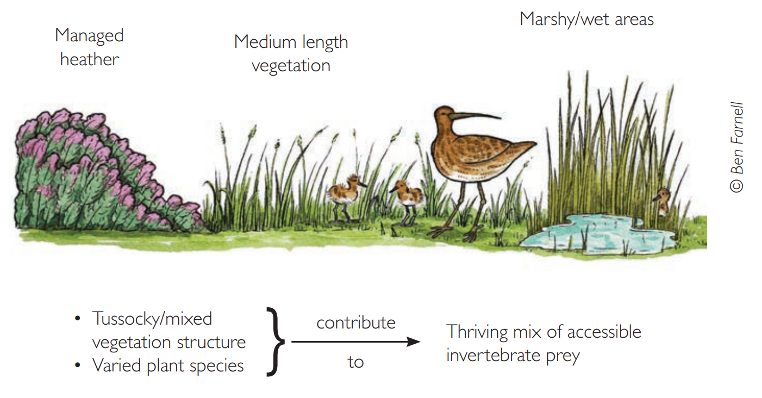

What conditions do curlew need for breeding?

Curlew are ground-nesting birds. They rely on carefully selected habitat in which to incubate their camouflaged eggs, raise chicks, and avoid predators8,26. They breed in upland moors, lowland heaths, bogs and wetland, rough pasture, and tussocky grasslands with mixed height vegetation, where there is little disturbance1,8 (see Figure 2). They may tolerate some short scrub but woodlands tend to be avoided8. Adult curlew often feed in farmed meadows and pastures that are adjacent to breeding habitat27.

Curlew are usually site-faithful, with pairs returning to the same nesting area every spring once they reach a breeding age at two years. Because of this, long-term maintenance of habitat quality and extent is important15.

The impact of afforestation on breeding curlew

Why, how and where is afforestation happening?

Trees provide numerous environmental, social, and economic benefits, and tree planting is widely considered to be one of the most important ways to combat climate change and poor air quality.

Afforestation in England is increasing on an annual basis and is a high priority for the government28. The target rate of tree planting is currently 30,000ha per year28, but this is set to increase after 202529. The England Tree Action Plan aims to increase the total wooded area in England from 10% to 12% by 205030.

Afforestation schemes in England operate at a range of scales, all of which contribute to the national target. For example, there are small-scale projects to increase urban tree cover in towns, right up to regional plans to plant thousands of hectares of trees in river catchments. These schemes are funded by a mixture of government, private and charitable sector sources31.

What significant issues will tree planting address? |

|

The government’s 25-year plan states that it will “incentivise planting on private and least-productive agricultural land where appropriate”37. Privately owned farmland covers 71% of the country36, therefore this land will be an important contributor to national afforestation targets.

Private landowners in England are being encouraged to apply for the Forestry Commission’s Woodland Creation Offer and Woodland Carbon Code schemes31. There is also a fast-emerging Natural Capital and Biodiversity Net Gain market, which will allow property developers and companies to approach private landowners to offset their environmental impact, which will incentivise afforestation on private land38.

In northern England the total woodland coverage is lower than the national average (7.6% compared to 10%)39. Planting in this region is a priority according to a government-funded project called the Northern Forest, which aims to plant 50 million trees across Yorkshire, Lancashire, Nottinghamshire, and Lincolnshire39. The project area includes part of the Pennines and North York Moors which support some of the country’s most important breeding wader populations16.

How does afforestation affect breeding curlew?

The decline in curlew is strongly associated with increased amounts of woodland near breeding sites22,40.

When afforestation takes place in open landscapes where previously there were few or no trees, the structure and species composition of the area rapidly transforms, which can make it unsuitable for curlew40. This can directly displace curlew through habitat loss, and also causes fragmentation of open breeding habitat. Fragmentation can expose more open land to ‘edge effects’, which are impacts occurring in a zone between suitable and unsuitable habitat8.

Afforestation causes two main edge effects which can negatively impact breeding waders:

- Increased avoidance of trees and forested areas40 leading to reduced area of breeding habitat

- Increased activity of mammalian and avian predators23,40-42 leading to reduced breeding success

The combination of habitat loss, fragmentation and resultant edge effects reduce the quantity and quality of the open breeding habitat in which curlew can successfully nest and rear chicks.

Study Spotlight |

| A 2022 study discovered that densities of most waders present on open breeding habitat within 200m of forestry plantations were under half of those 700m away23. The researchers found that planting a large, 1000ha block of woodland instead of planting 50, 20ha blocks can reduce the resultant decline of waders by 50%. The study was undertaken in Iceland, which has an important assemblage of breeding waders including many of the species found in the UK. |

How does afforestation affect predation of curlew nests?

Predation from mammals and birds can limit curlew breeding success9,43,44, with predation being a major cause of nest failure6,7,45,46. Red foxes and corvids are the main predators of curlew nests in many areas, and both are known to occur in higher densities in fragmented wooded landscapes compared to open landscapes7,22.

The predation pressure in the zone surrounding a woodland is sometimes referred to as a ‘predator shadow’47. A predator shadow can be created or expanded when afforestation takes place in an area with breeding waders42. This may occur if numbers of foxes and corvids increase in size due to woodland expansion, or new animals colonise new woodland plots11.

There have been some key scientific studies into the relationship between nest predation and afforestation:

- A 2020 study found that numbers of mammalian predator scats were nearly 3 times higher in open breeding habitat that had above 10% land cover of forestry within 700m than in areas with less41. This supports earlier findings that breeding waders occur in reduced densities when forestry plantations were present within 700m48.

- A 2014 study found that curlew abundance and nesting success were positively related to predator control (by gamekeepers) and negatively affected by woodland within 1km of nest sites (as a likely source of predators)40. To stabilise curlew numbers, the study found that predator control effort would need to increase by nearly 50% to offset the impacts of increasing woodland cover from 0% to 10% within 1km of curlew breeding sites.

- A 2010 study found that predation of bird nests is more common in areas of increased forest plantation cover42. Predation seems to be more strongly related to landscape composition than to proximity of nests to woodland. Predator foraging behaviour – as opposed to abundance – may be an important factor in explaining nest predation.

GWCT research into predator behaviour supports the latter statement. Between 2015 and 2019 in the Avon Valley in southern England, GWCT scientists fitted 37 adult foxes with GPS collars to explore their movement behaviour in habitats important for breeding waders. Initial analysis of GPS location data shows that foxes tend to navigate along linear features such as tracks, field-edges and waterways (M. Short, GWCT, in press). This is significant because new afforestation programmes are likely to create new fox movement highways such as machinery tracks and access paths near breeding wader habitats, which will increase predation risk.

| Knowledge gaps |

Identified by Defra/Natural England/Forestry Commission49:

|

Official guidance for woodland creation

The Forestry Commission and Natural England have worked with the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) and Defra to design a step-by-step process for applicants of woodland planting schemes to follow. It makes use of the latest BTO distribution and population density data for breeding waders. The guidance is designed to help applicants and their advisors anticipate impacts on wading birds, in order to avoid harmful proposals and apply mitigation where necessary.

The official Defra guidance was published in August 2022 and is available in full on the GOV.UK website along with frequently asked questions. It will be reviewed periodically to incorporate new evidence and feedback. The guidance is currently geared towards woodland projects in the North of England and primarily focuses on curlew, redshank and lapwing.

| Summary of Defra guidance47,49 |

Step 1

|

Conclusion

There are gaps in our knowledge about the conservation of curlew and the management of their open habitat, but a reasonable body of scientific evidence underpins the concern that afforestation is a significant threat to breeding curlew and other waders. The science concludes that a key aspect of this threat is the increased predation of curlew nests.

At the same time, it is clear that, to meet the national climate and biodiversity targets, we need to plant more trees. The new afforestation guidance will enable those involved in woodland planting schemes to put the right trees in the right places. This way, it may be possible to strike a balance between this need for rapid expansion of tree cover, with the national and international obligation to protect curlew.

Donate and help us fight misinformation

Further reading: Graham Appleton’s WaderTales blog contains useful summaries of relevant wader research.

References

- Curlew Bird Facts | Numenius Arquata – The RSPB. Available at: https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/wildlife-guides/bird-a-z/curlew/. (Accessed: 27th July 2022)

- Woodward, I., Aebischer, N., Burnell, D., Eaton, M., Frost, T., Hall, C., Stroud, D.A. & Noble, D. (2020). Population estimates of birds in Great Britain and the United Kingdom. British Birds, 113:69–104.

- Curlew Recovery Partnership. Introducing Curlews. Available at: https://www.curlewrecovery.org/_files/ugd/3df746_fd4f54f5b9f4432685938cf94a27c1d0.pdf. (Accessed: 27th July 2022)

- Harris S.J., Massimino, D., Balmer, D.E., Kelly, L., Noble, D.G., Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Woodcock, P., Wotton, S. & Gillings, S. (2022). The Breeding Bird Survey 2021. BTO Research Report 745. Thetford, UK.

- Robinson R.A. BTO BirdFacts | Curlew. BirdFacts: profiles of birds occurring in Britain & Ireland.: Available at: https://app.bto.org/birdfacts/results/bob5410.htm. (Accessed: 27th July 2022)

- Fletcher, K., Aebischer, N.J., Baines, D., Foster, R. & Hoodless, A.N. (2010). Changes in breeding success and abundance of ground-nesting moorland birds in relation to the experimental deployment of legal predator control. Journal of Applied Ecology, 47:263:272.

- Valkama, J., Currie, D. & Korpimäki, E. (1999). Differences in the intensity of nest predation in the curlew Numenius arquata: A consequence of land use and predator densities? Ecoscience, 6:497-504.

- Brown, D. (2015). International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Eurasian Curlew. AEWA Technical Series No. 58. Bonn, Germany.

- Roodbergen, M., van der Werf, B. & Hötker, H. (2012). Revealing the contributions of reproduction and survival to the Europe-wide decline in meadow birds: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Ornithology, 153:53–74.

- Valkama, J., Robertson, P. & Currie, D. (1998). Habitat selection by breeding curlews (Numenius arquata) on farmland: The importance of grassland. Annales Zoologici Fennici, 35:141-148.

- Douglas, D.J.T., Bellamy, P.E., Stephen, L.S., Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Wilson, J.D. & Grant, M.C. (2014). Upland land use predicts population decline in a globally near-threatened wader. Journal of Applied Ecology, 51:194-203.

- Wilson, J.D., Anderson, R., Bailey, S., Chetcuti, J., Cowie, N.R., Hancock, M.H., Quine, C.P., Russell, N., Stephen, L. & Thompson, D.B.A. (2014). Modelling edge effects of mature forest plantations on peatland waders informs landscape-scale conservation. Journal of Applied Ecology, 51:204-213.

- Wilson, M., Wetherhill, A., Calladine, J., Hetherington, D., Boyd-Wallis, W., Cottam, M., Drewitt, A., Jowitt, A., Cussen, R., Findlay, J., McGugan, A., Hall, J., Perkins, A., Bailey, C., Bellamy, P., Tomes, D., Phillip, A., Douglas, D., Orr-Ewing, D., Newey, S., McLeod, R., Tharme, A., Franks, S., Taylor, R., Pearce-Higgins, J., Jarrett, D. & Wernham, C. (2021). Sensitivity mapping for breeding waders in Britain: towards producing zonal maps to guide wader conservation, forest expansion and other land-use changes. Report with specific data for Northumberland and north-east Cumbria.

- Sutherland, W.J., Alves, J.A., Amano, T., Chang, C.H., Davidson, N.C., Max Finlayson, C., Gill, J.A., Gill, R.E., González, P.M., Gunnarsson, T.G., Kleijn, D., Spray, C.J., Székely, T. & Thompson, D.B.A. (2012). A horizon scanning assessment of current and potential future threats to migratory shorebirds. Ibis, 154:663–679.

- Brewin, J. (2017). Conserving the Curlew. Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust, Fordingbridge, Hampshire.

- Colwell, M., Hilton, G., Smart, M. & Sheldrake, P. (2020). Saving England’s lowland Eurasian Curlews. British Birds, 113:279–292.

- Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act 2006. Section 41: Biodiversity lists and action (England): Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/16/section/41. (Accessed: 17th August 2022)

- Stanbury, A., Eaton, M., Aebischer, N., Balmer, D., Brown, A., Douse, A., Lindley, P., McCulloch, N., Noble, D. & Win I. (2021). The status of our bird populations: the fifth Birds of Conservation Concern in the United Kingdom, Channel Islands and Isle of Man and second IUCN Red List assessment of extinction risk for Great Britain. British Birds, 114:723–747.

- Balmer, D., Gillings, S., Caffrey, B., Swann, B., Downie, I. & Fuller, R. (2013). Bird Atlas 2007–11: the breeding and wintering birds of Britain and Ireland. British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) Books. Thetford, UK.

- Wilson, M., Pearce-Higgins, J., Franks, S. & Noyes, P. (2020). Audit of local studies of breeding Curlew and other waders in Britain and Ireland. BTO Research Report. No. 727. Thetford, UK.

- Taylor, R. & Dodd, S. (2013). Negative impacts of hunting and suction-dredging on otherwise high and stable survival rates in Curlew Numenius arquata. Bird Study, 60:221–228.

- Franks, S.E., Douglas, D.J.T., Gillings, S. & Pearce-Higgins, J.W. (2017). Environmental correlates of breeding abundance and population change of Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata in Britain. Bird Study, 64:393-409.

- Pálsdóttir, A.E., Gill, J.A., Alves, J.A., Pálsson, S., Méndez, V., Ewing, H. & Gunnarsson, T.G. (2022). Subarctic afforestation: Effects of forest plantations on ground-nesting birds in lowland Iceland. Journal of Applied Ecology, doi:10.1111/1365-2664.14238

- Wilson, M., Wetherhill, A., Calladine, J., Hetherington, D., Boyd-Wallis, W., Cottam, M., Drewitt, A., Jowitt, A., Cussen, R., Findlay, J., McGugan, A., Hall, J., Perkins, A., Bailey, C., Bellamy, P., Tomes, D., Phillip, A., Douglas, D., Orr-Ewing, D., Newey, S., McLeod, R., Tharme, A., Franks, S., Taylor, R., Pearce-Higgins, J., Jarrett, D. & Wernham, C. (2021). Sensitivity mapping for breeding waders in Britain: towards producing zonal maps to guide wader conservation, forest expansion and other land-use changes. Report with specific data for Northumberland and north-east Cumbria.

- Ludwig, S.C., Roos, S. & Baines, D. (2019). Responses of breeding waders to restoration of grouse management on a moor in South-West Scotland. Journal of Ornithology 2019 160:3, 160:789–797.

- Five forest birds that nest on the ground | Forestry England. Available at: https://www.forestryengland.uk/blog/five-forest-birds-nest-ground. (Accessed: 8th August 2022)

- Johnstone, I., Elliot, D., Mellenchip, C. & Peach, W.J. (2017). Correlates of distribution and nesting success in a Welsh upland Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata population. Bird Study, 64:535–544.

- Policy Paper: Nature for people, climate and wildlife – GOV.UK. Defra: Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nature-for-people-climate-and-wildlife/nature-for-people-climate-and-wildlife. (Accessed: 17th August 2022)

- National Audit Office. (2022). Planting trees in England. London.

- England Trees Action Plan 2021 to 2024 – GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/england-trees-action-plan-2021-to-2024. (Accessed: 18th July 2022)

- Tree planting and woodland creation: funding and advice – GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/tree-planting-and-woodland-creation-funding-and-advice. (Accessed: 11th August 2022)

- UK becomes first major economy to pass net zero emissions law – GOV.UK. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-becomes-first-major-economy-to-pass-net-zero-emissions-law. (Accessed: 11th August 2022)

- UK natural capital: ecosystem accounts for freshwater, farmland and woodland. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/bulletins/uknaturalcapital/landandhabitatecosystemaccounts. (Accessed: 23rd June 2022)

- Biodiversity: why native woods are important – Woodland Trust. Available at: https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/blog/2020/07/biodiversity-and-native-woods/. (Accessed: 11th August 2022)

- Forests for wellbeing | Forestry England. Available at: https://www.forestryengland.uk/wellbeing. (Accessed: 31st August 2022)

- Defra & Government Statistical Service. (2021). Agriculture in the UK Evidence Pack . Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1027599/AUK-2020-evidencepack-21oct21.pdf. (Accessed: 11th August 2022)

- Defra. (2018). A Green Future: Our 25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment. London.

- Baker, J., Hoskin, R. & Butterworth, T. (2019). Biodiversity Net Gain. Good practice principles for development A practical guide. London.

- The Northern Forest: Planting 50 Million Trees | The Woodland Trust. Available at: https://thenorthernforest.org.uk/. (Accessed: 17th August 2022)

- Douglas, D.J.T., Bellamy, P.E., Stephen, L.S., Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Wilson, J.D. & Grant, M.C. (2014). Upland land use predicts population decline in a globally near-threatened wader. Journal of Applied Ecology, 51:194–203.

- Hancock, M.H., Klein, D. & Cowie, N.R. (2020). Guild-level responses by mammalian predators to afforestation and subsequent restoration in a formerly treeless peatland landscape. Restoration Ecology, 28:1113–1123.

- Reino, L., Porto, M., Morgado, R., Carvalho, F., Mira, A. & Beja, P. (2010). Does afforestation increase bird nest predation risk in surrounding farmland? Forest Ecology and Management, 260:1359–1366.

- Brown, D., Wilson, J., Douglas, D., Thompson, P., Foster, S., Mcculloch, N., Phillips, J., Stroud, D., Whitehead, S., Crockford, N., Sheldon, R., Mclean, P. & Flpa, /. (2015). The Eurasian Curlew-the most pressing bird conservation priority in the UK? © British Birds, 108:660–668.

- Grant, M.C., Orsman, C., Easton, J., Lodge, C., Smith, M., Thompson, G., Rodwell, S. & Moore, N. (1999). Breeding success and causes of breeding failure of curlew Numenius arquata in Northern Ireland. Journal of Applied Ecology, 36:59–74.

- MacDonald, M.A. & Bolton, M. (2008). Predation on wader nests in Europe. Ibis, 150:54–73.

- Zielonka, N.B., Hawkes, R.W., Jones, H., Burnside, R.J. & Dolman, P.M. (2019). Placement, survival and predator identity of Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata nests on lowland grass-heath. Bird Study, 66:471–483.

- Defra, Forestry Commission & Natural England. (2022). Guidance to help inform when an upland breeding wader survey is needed and when woodland creation is likely to be appropriate. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1097668/August_2022_Wader_Guidance_FINAL_V3.1.pdf. (Accessed: 17th August 2022)

- Hancock, J.M.H., Grant, M.C. & Wilson, J.D. (2009). Associations between distance to forest and spatial and temporal variation in abundance of key peatland breeding bird species. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00063650802648176, 56:53–64.49.

- Defra, Forestry Commission & Natural England. Upland Breeding Wader Guidance: Frequently Asked Questions – GOV.UK. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1097670/FAQ_V2.pdf. (Accessed: 17th August 2022)